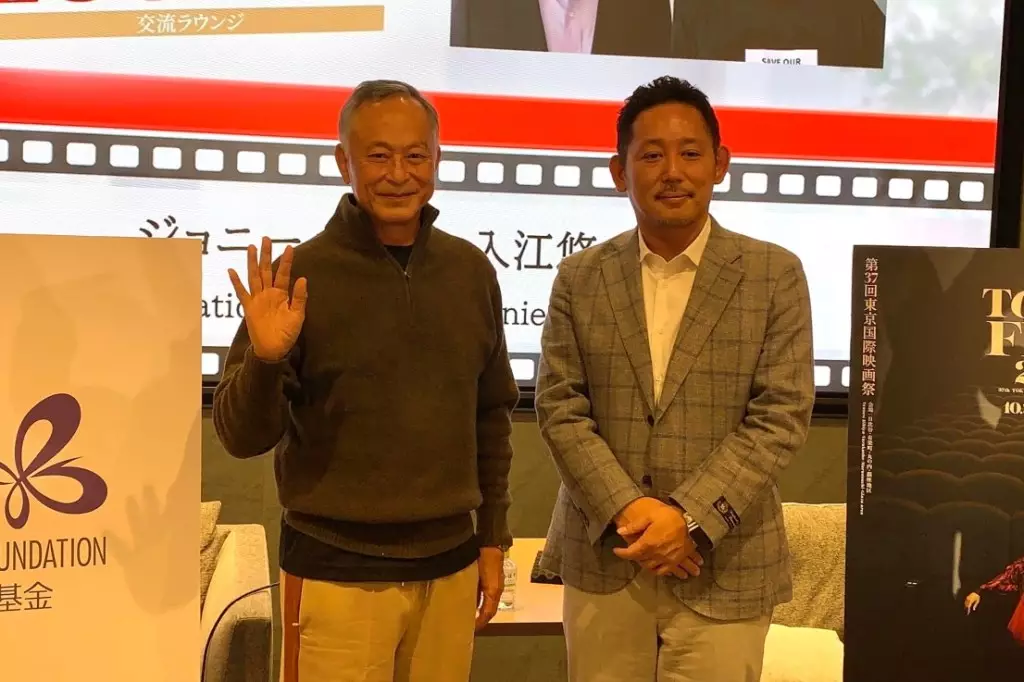

At the Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF), esteemed Hong Kong filmmaker Johnnie To engaged in an insightful dialogue with Japanese director Yu Irie. Their conversation not only highlighted To’s remarkable career but also served as a reflection on the shifting landscape of filmmaking in Hong Kong. The discussion took place in TIFF’s Nippon Cinema Now section, where Irie expressed his admiration for To’s influential films such as *Exiled* and *The Mission*. The exchange was not merely a celebration of To’s accomplishments but also a critical analysis of the constraints modern filmmakers face in the changing sociopolitical environment of Hong Kong.

To’s distinctive approach to filmmaking is characterized by a more spontaneous, improvisational style, often eschewing traditional screenplays. In his perspective, adhering strictly to a fixed script can stifle creativity. “Creating a proper screenplay before you start shooting means that the movie is already completed,” he remarked, indicating that he prefers to keep the film’s essence fluid and alive during the shoot. With every project, To intuitively understands the beginning and end of scenes, allowing his creativity to flourish organically.

While this method has yielded compelling results, To himself acknowledged the risks associated with such a free-wheeling style. “It’s probably not the best style of filmmaking,” he cautioned, implying that it may not suit every budding director. His admission underscores the importance of adaptability in the industry—a theme that resonates especially today given the challenges faced by filmmakers in Hong Kong.

The conversation also touched upon To’s unorthodox practice of working on multiple films at once. This approach allows him to explore different thematic and stylistic avenues concurrently, enriching his filmmaking palette. He candidly shared his experiences of managing different projects, stating that “it would be like one commercial movie, one more personal, perhaps another film as well.” This versatility in directing not only showcases his broad skill set but also reflects a deeper understanding of the various aspects of storytelling in film.

To’s work on *Sparrow*, for example, illustrates this multifaceted approach. He explained how financial constraints led him to alternate between projects, shooting other films to fund the completion of *Sparrow*, which took two to three years to finish. Such stories reveal the resilience and resourcefulness required to navigate the modern cinematic landscape, especially within the framework of Hong Kong’s evolving film culture.

A poignant theme that emerged from the conversation was the encroaching censorship in Hong Kong’s film industry. To voiced concerns regarding the diminished creative freedoms faced by filmmakers today, attributing these constraints to increased regulations from Beijing. He reflected on recent events wherein several films at Hong Kong’s Fresh Wave International Short Film Festival faced censorship, with certain scenes blacked out or muted. This level of governmental oversight poses serious challenges for artists striving to express their narratives authentically and courageously.

To encapsulated this sentiment by stressing the need for filmmakers to comprehend the nuances of censorship: “If you’re trying to create a film, you have to be ready to understand how the censorship is working.” This awareness doesn’t just foster survival but can fuel creative efforts to convey meaningful messages within the confines of current regulations.

Despite these bleak realities, To remains optimistic about the future of cinema, particularly for young filmmakers. Addressing the next generation of artists, he encouraged them to seek opportunities beyond Hong Kong. “If you can’t create the film in Hong Kong, make it in Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, or even here in Japan,” he advised, advocating for a broader geographic approach to filmmaking. This advice underscores the importance of resilience, adaptability, and expanding horizons in an industry increasingly characterized by limitations.

In highlighting the significance of talent over location, To conveyed an inspiring message: “It’s up to you to make it happen, but you have to do it in a smart way.” For To, the true essence of filmmaking transcends geographical boundaries, with passion and talent serving as the key drivers for success in an evolving film landscape.

Finally, in a bid to revitalize the Hong Kong film industry, To called for more investment—both from government and private sectors. He emphasized that sustainable growth and opportunities for emerging filmmakers hinge upon adequate funding and resources. As he nears his 70s, To’s commitment to nurturing new talent remains unwavering, and his insights represent both a celebration of his legacy and a roadmap for future filmmakers.

Ultimately, Johnnie To’s conversation at TIFF served as a powerful reminder of the enduring spirit of cinema, even in the face of adversity. His journey encourages filmmakers to embrace their unique visions while navigating the complexities of the modern world, ensuring that the legacy of Hong Kong cinema continues to thrive.